Stories need to have a beginning, a middle, and an end.

These words go back to Aristotle and his observations on tragedy. Recently, I saw them displayed prominently on the submission page of a magazine. I thought: duh, do writers have to be reminded of this? Then I remembered a few stories I read that left me scratching my head. What was the point, where was the story? I don’t mind moody yarns, vignettes, or post-modern narratives, just not all the time. There is strength in classic storytelling, following what is often called the three-act structure:

Act 1: Set-up - exposition, inciting incident, plot point 1

Act 2: Confrontation - action, raising the stakes (crisis), plot point 2

Act 3: Resolution - pre-climax, climax, epilogue

You’ll find an excellent overview on The Masters Series website (no need to be enrolled in a class to have access to it), and I’m not going to repeat what the people over there explain so well. Of course the 3-acts thing is not as mechanical and militaristic as it appears. Sub-plots, twists and turns, highs and lows are sprinkled all across the book, play, or movie.

We are so used to this way of telling a story that we don’t notice the props behind the production. And good writers are skilled at hiding their hand. When the scaffolding shows, we cringe and complain about clichés and tired tropes. I’ve read this story before, we say.

The principles of the 3 acts are simple but the execution isn’t. Each step presents difficulties for the writer. These are the ones I am familiar with. I’m sure there are other pitfalls that don’t come to mind right now. Please feel free to share your insights in the comments.

The sins of Act 1: Confusion and long-windedness

Starting a story is exciting and the first pages fly off the keyboard. Even the most dedicated improvisers know enough about the general lean of the book to get off to a sparkling start. I think it’s James Lee Burke who said he always knows 1 or 2 chapters ahead. He doesn’t see the entire road but he sees what’s in the headlights. Many writers function this way. At the polar opposite there’s the super-organized brigade that has every little detail nailed down, to the page number. Frankly, that would scare me. I would grow tired of the book before it’s even written.

But, but … the compulsive planners are less likely to fall into the traps of Act 1 (or 2 and 3, for that matter).

Namely: Too much exposition. We’re all familiar with the first chapters (or, hark, The Prologue!) overloaded with background, so bloated with information about people, places, and past events that the poor reader has no idea what the story’s all about. In science fiction or fantasy, it’s almost inevitable. There’s a whole strange universe to bring to life and the background to go with it. It’s that scrolling text at the beginning of Star Wars – A new Hope. In general, it’s better to jump straight in with as little exposition as possible. The information can be distilled throughout the story.

Another frequent problem in Act 1 is too many characters introduced too fast. Anna, the daughter of George and Mary, is Judy’s sister-in-law, with two kids named Aidan and Emily, married to Joe who’s a computer analyst with BumbleBlog based in … Time-out: who is this person again?

And then there’s the cardinal sin of a slow, so slow entry into the story that the reader’s mind wanders. If you think that’s a modern attention deficit issue, think again.

I have just returned from a visit to my landlord—the solitary neighbor that I shall be troubled with.

That’s the first line of Emily Brontë’s Wuthering Heights, and she introduces Heathcliff in paragraph two. So much for slow-burning Victorians.

I remember hearing an editor (or was it an agent?) say that writers should delete the first 50 pages because that’s where the real story starts.

The opposite of the peripatetic start can also create trouble. A wham-bam beginning that fizzles by chapter 3, but maybe by then the reader is prepared to go with you a bit longer.

The morass of Act 2: Fatigue and aimlessness

This is where stuff really gets tricky. Writers call it The Muddy Middle, or The Sagging Middle. It’s where stories go to sleep. You have a good thing going, the plot is churning, and then … it … grinds … to … a … halt. Lethargy verging on the catatonic. Because there’s only so much you can throw at the protagonists, so many wrenches you can stick in the gears, so many problems you can create before the entire plot looks like a porcupine with a messy haircut.

The yawn midway through the yarn sinks books. Or movies. That’s when, if you’re watching a film at home, you feel the need for a snack or a bathroom break. Because you know you’re not missing anything major. I don’t have a secret recipe to avoid the dip in attention. A little pause in the shenanigans, a moment to take a breather, maybe a short flashback are not bad things. Readers need breaks, like musical pieces need silences. The danger is in the rambling and a plot that loses its way. What works best for me is to finish the first draft and then let it sit, not even think about it, for at least a month. It does wonders to spot the weak spots that either need to be spruced up or savagely cut. As Elmore Leonard said: Remove the boring parts.

Act 3: Sticking the landing

By then, readers have spent hours with the story, they’re invested in the characters, they have built their own vision of how it all comes together. The writer has been immersed in it even longer. So far, cross fingers, I haven’t had problems with endings. Before the final climax, I have a good idea of how the story will end. Details may change as events unfold and characters react and talk, but the broad picture is in place. I know when I have an ending that works. It makes a distinct sound. Crisp. That doesn’t mean that all the issues raised in the book are resolved. In crime fiction, ambiguity rules. It’s important, however, to avoid dangling threads and inconsistent plot points. Open questions are all right.

The biggest problem, in my opinion, is a rushed ending. After 300 pages, the writer’s getting impatient and wants to close the deal. It’s like spending hours cooking an elaborate meal and eating it in five minutes because you have a plane to catch. It’s a pace and a rhythm thing. Stories end when the time is right, they cannot be forced. If it takes two more chapters, so be it.

But, liking or not liking an ending is highly subjective.

Paul Tremblay’s The Cabin at the End of the World got a lot of flak for its ending but I like it. On the other hand, I’m not a fan of the way Jordan Harper concludes Everybody Knows. And I didn’t like the end of Stephen King’s The Outsider, even if I don’t know how he could have done it any other way. That doesn’t mean I didn’t enjoy the books. There’s just that little pinch …

This is it, friends, ramblings on beginning, middle, and end.

1, 2, 3. So what’s the 4 in the title of this newsletter for?

The fake ending. The addendum. Horror movies do it all the time. The monster is dead, the plucky protagonist got away, but wait … In books, one example is the clever afterword in Chasing the Boogeyman by Richard Chizmar. I won’t tell you what that fourth act is about. The eBook reader says Book Complete. Ahah, not so fast ...

That’s it for this issue. See you soon. And take a peek at the stories below the picture.

Short stories

It has been a busy April on the short story front.

Signed, Joey was published by Apocalypse Confidential. It’s a fun one and free to read.

He leaned closer to the frame. “It’s annoying,” he said. “There’s no price. I believe things should be priced, so you would know ahead of time if you can afford to fall in love with them or not.”

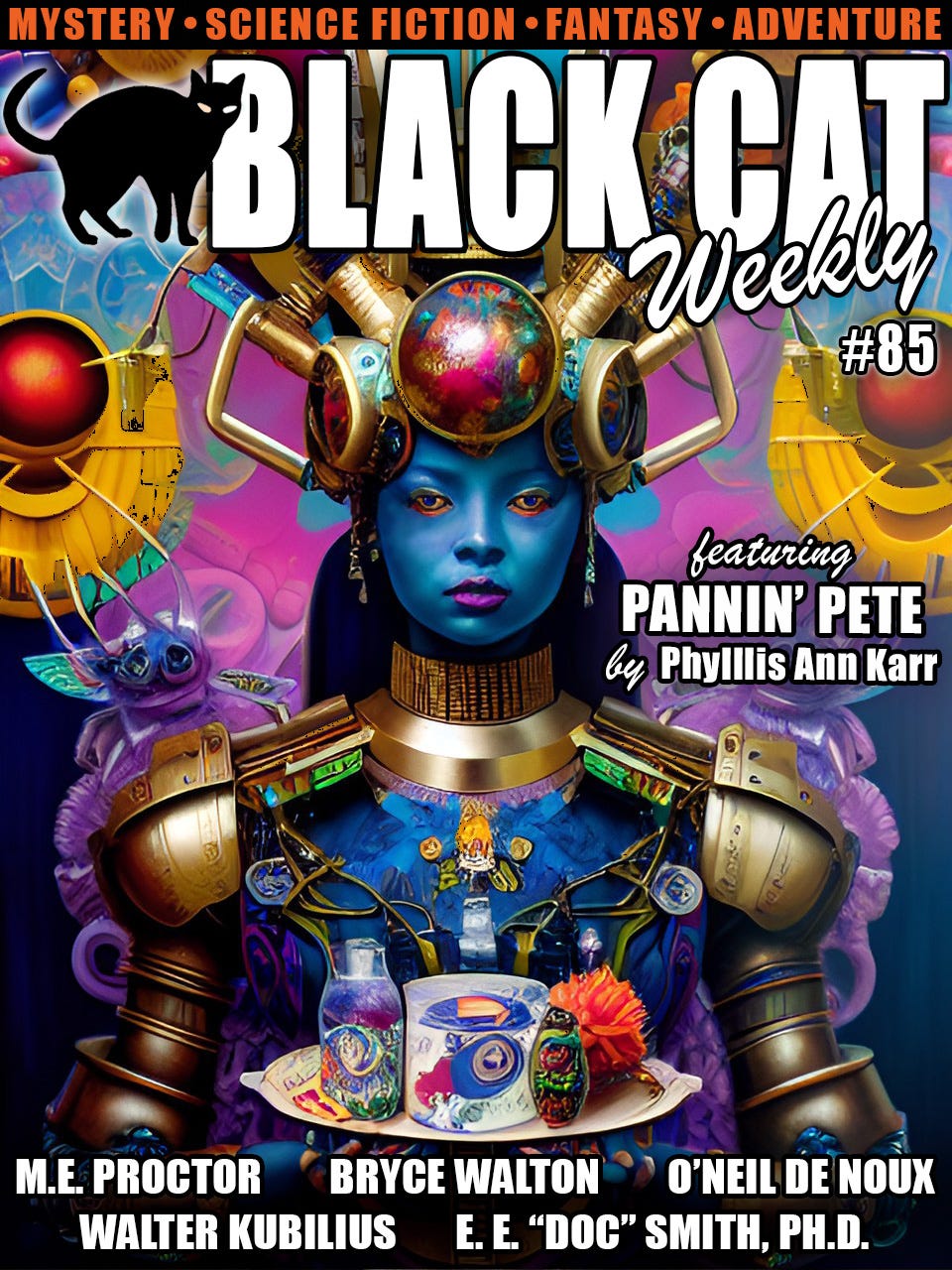

Cottonmouths, a PI story with an East Texas flavour, is in Black Cat Weekly #85. Nice to be on that wild cover!

Nobody had lived in the Crawford house for at least ten years. It was an eyesore, the roof had caved in on one side, the walls were full of holes and streaked with mold black as soot, with Virginia creeper and poison ivy poking through the cracks. It was amazing no kid had yet sent a firebomb flying into it. Leon was tempted to give it a go. He’d always wondered what sending a Molotov cocktail soaring felt like. Something he should check off his bucket list before it was too late for him to throw anything.

Havok published Where the Gods Live. That’s behind a paywall, so I can only share the main link. Maybe it’ll make it into an anthology, we’ll see.

Obviously (I think?) a 1-2-3 structure might look different in a novel than a short story. There are tricks a writer can do to play with time... events seeming to be concurrent but in fact separated out, for example. I think part of the Muddy Middle is also reflective of the process. The writer tends to be invested in that beginning, but then (especially, if you are like me and haven't thought it all the way through), you might get lost in the weeds of the story. I'm sad to say I've abandoned more than one WIP part way through because I, as the writer, wasn't invested anymore, so how could I expect my readers to be?

There's a certain advantage to world building "off the main page" so that you can then work those details in slowly but surely, seasoning and seeding throughout the story to avoid unseemly clumps of infographics. I am slowly working at being less of a pantser as I progress through my own writing journey. We'll see how that goes.

Love the cover of Black Cat Weekly! Congrats on published pieces, Martine! Must take closer looks...