I dedicated Love You Till Tuesday (the first Declan Shaw PI novel) to my dad. He was a compulsive reader of romans policiers (crime stories) and when we didn’t watch crime movies together, we watched westerns, that are, for all intent and purpose, crime films with horses. Dad didn’t bring his job home—he was an inspecteur de police (detective) and retired with the rank of commissaire. He didn’t tell us kids about the stuff he dealt with at work. Except once. That episode inspired the story below. Dun dun.

Lit Up* was published four years ago in Punk Noir Magazine. It is the first appearance of homicide detective Tom Keegan of the San Francisco Police Department. The year is 1950. Tom is one of the main protagonists in the recently published Bop City Swing.

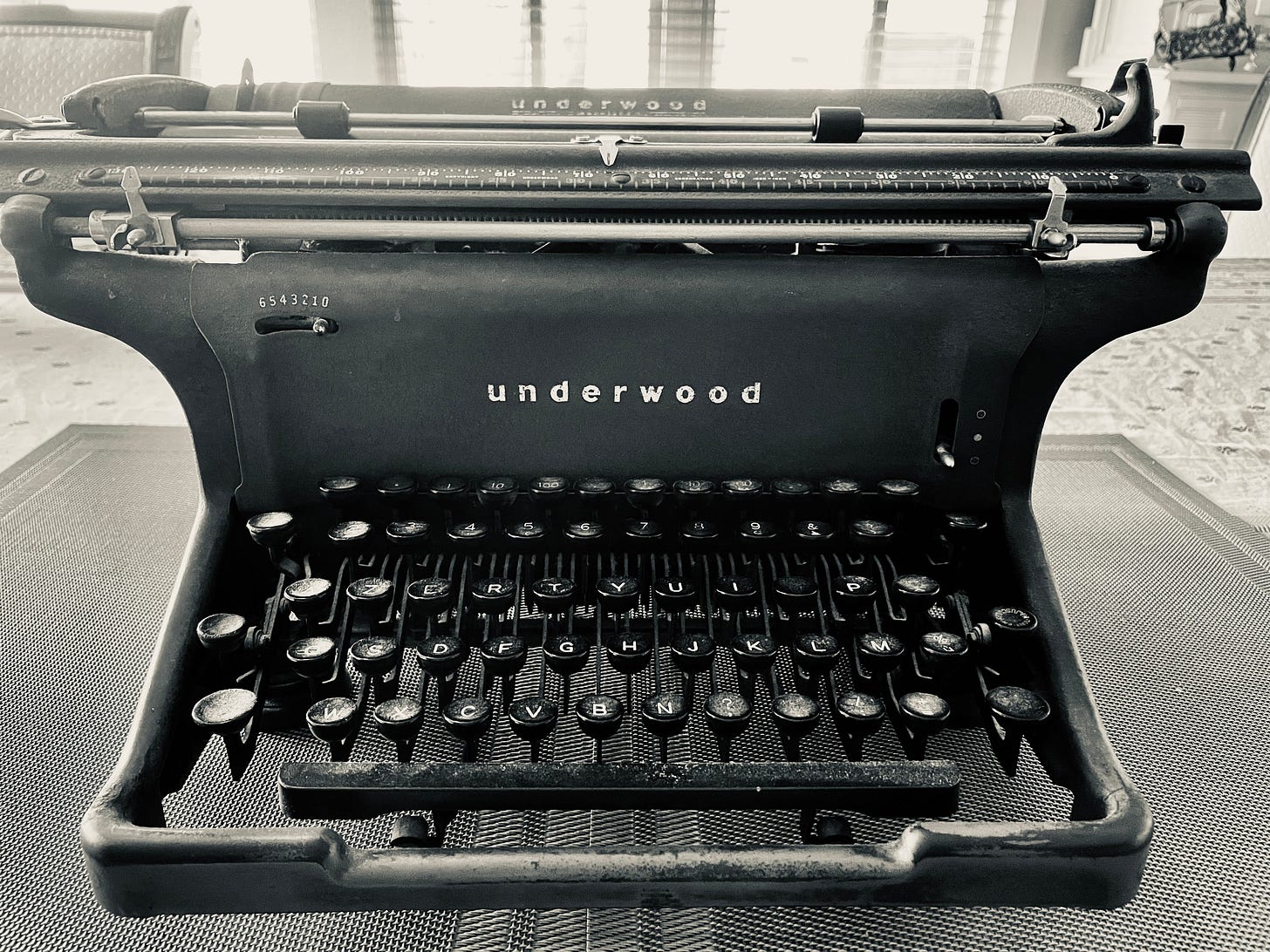

I thought you might want to get acquainted … I still have the Underwood that belonged to Dad, and even used it to write stories back in the day … clack, clack, ding. Photographic evidence below.

*(I changed a few things from the original text)

Lit Up

“I swear someday I’ll throw that piece of shit through the window,” Tom Keegan said. “And I won’t bother opening the damn window either.”

Al ‘Matt’ Matteotti looked up from his stack of notes. “Threatening violence against an inanimate object? Not to mention that this piece of shit is government property.”

“See if I care.” Tom had his fingers in the basket of the bulky Underwood, untangling the typebars. It was a familiar sight. So far, the Underwood was winning.

“You know what’s wrong with you?” Matt said.

Tom slid the carriage, making the boxy thing go ding. “Enlighten me.” He worked the lever return to get back to the right spot in the document. “Damn nuisance.”

“It jams because you type too fast. You’re too impatient. You confuse the stupid contraption. Me, on the contrary …” Matt raised his index finger, held it up in the air until Tom turned to look at him “One finger. See.” He switched to the middle finger, flipping the bird. He talked as he typed. “R – clack – O – clack – B – clack – E – clack – R – clack – Y – clack. No jam, no tangle. Slow and steady does it.”

“There’s two Bs in Robbery, you dolt,” Tom said. “It’s written on the door. Right there.” He pointed at the office door. “You go through it a hundred times a day.”

“So?” The phone on Matt’s desk rang and he stared at it. “What’s it gonna be today? Jumper, floater, skeleton in closet? These people we’re sworn to serve and protect are tiresome.” He picked up the phone. “Detective Matteotti.”

Tom was about to give the typewriter another try when Helen walked in, prim and put together, as always, in her no-nonsense brown suit. She was on her way to the Chief’s office with a stack of reports.

“Helen, honey,” he said. “A little help here.”

She turned on her sensible heels. “Like what?”

Tom pointed at the typewriter. “This clunker drives me nuts.”

“Put in a requisition.”

They both knew that wasn’t going to go beyond the rim of a waste basket. “Listen, if I could …”

“Tommy! Gotta go.” Matt slammed the phone down. He was out of his chair, at the coat rack, grabbing his jacket, stuffing a notepad in the pocket, giving his hat a good push down. “Andiamo, we have a hot one.”

Tom gave Helen another pleading look. “My report’s here, babe. It’s clear, readable, pretty as sin. It would take you ten minutes tops, I promise.”

“You must be kidding.” She stood with one fist on her hip, indignant.

Tom reached up to catch his hat that Matt had sent sailing through the room. “Dinner and a movie. On my dime. You pick the place.” He shot her his brightest smile and rushed after Matt who was already in the corridor, halfway to the elevator.

“You have no shame,” Matt said. “Putting the moves on your own sister.”

The radio squawked and they both ignored it. Matt drove. He was by far the better driver. He said all Italians were born with a steering wheel between their little mitts and a gear stick for a pacifier. Most cops hated riding shotgun with Matt. Tom found it liberating. The ride was so hair rising, he had no time to think about anything else. It cleared his head.

“Where are we going?”

“The Mission,” Matt said. “Something crispy.”

“Arson?”

“From what the trooper said, I doubt it. A roasted body, nothing else damaged.”

“Fuck, Matt! I hate those.” Tom closed his eyes. A tight curve sent him slamming into the door. He ought to keep his eyes on the road. “You should have taken Orlov.”

“Dee-fective Orlov is a brick.” Matt tapped the side of his head with a knuckle. “And you’re my partner.” He flashed a big white-toothed grin. “It is a mistero. You like those, no?”

Not when it involved cremated bodies. Tom saw enough of those in the camps. Too recently to have forgotten. As if that could ever be forgotten. “If I barf all over your mistero, it’s on you.”

Matt reached for the glove box, and retrieved a jar of Vicks. He dropped it in Tom’s lap. “Never leave home without it.”

Spoken from experience. Tom had seen his partner lose his lunch a couple of times. Matt hated small, dark, enclosed spaces. Everybody had their own flavor of things that went bump in the night.

“The doc’s on the way. We’ll beat him to it,” Matt said.

That explained why he was driving even more like Fangio than usual. Nothing pleased Matt more than being first on site. Considering how sloppily some cops treated crime scenes, he was not wrong.

“What else did the trooper tell you on the phone?” Tom said.

“Private residence. The housekeeper came in at ten. Her employer wasn’t home. She smelled something bad and found the body in the greenhouse.”

“A greenhouse? In town? Who’s the employer, some kind of garden freak?”

“Painter. Carlos Camacho. He lives alone.” Matt shrugged. “Lived. It’s likely he’s the corpse.”

Depending on the condition of the body, identification might take a while.

Matt slammed on the brakes in front of a two-story white-painted house in the pleasant Spanish style that went so well with clinging bougainvillea and lush shrubbery. The house was pretty, the landscaping neat. Carlos Camacho wasn’t a starving artist. A police cruiser was parked in the driveway. Clean and glossy. Didn’t look out of place.

“How do you want to play it?” Matt said.

“Let’s look around while we have the place to ourselves. Interviewing the housekeeper can wait.”

The trooper in the hallway looked a little green, mouth clenched, forehead coated with sweat.

“I’m Detective Keegan,” Tom said. “This is Detective Matteotti. You spoke to him on the phone.”

“Yes, sir. Officer Brockwoods, sir. I was in the neighborhood when the call came in. I put Mrs. Dantonio in the sitting room. Uh, she’s the housekeeper, she’s shook up.”

“We’ll be with her soon,” Matt said. “You went through the house?”

“To make sure there wasn’t anybody. I didn’t touch anything, and I watched where I put my feet, sir.”

Commendable. Tom nodded. The smell of paint and turpentine was strong. “The housekeeper told you she smelled something bad and went to look. Where was she?”

“The kitchen, sir.” The trooper pointed to the back of the house. “The kitchen connects with the greenhouse.”

“Stay here,” Tom said. “Let the medical examiner in, but nobody else unless I say so.”

The trooper looked uncomfortable. “Uh, I’ll try, sir.”

“Won’t be for long,” Matt said. “Tell them it’s that asshole Keegan having the vapors.”

As soon as they reached the kitchen, the stench was unmistakable. Tom clapped a hand over his nose, knowing full well that it wouldn’t do any good. His last two cups of coffee roiled. The camphor goop from the jar helped a little.

The door between the kitchen and the greenhouse was open. Matt went down on one knee next to a double set of footprints. The big ones to the side, the small ones in the middle of the kitchen. All prints came from the greenhouse and pointed toward the hallway. “Dirt from the garden. Trooper Brockwoods and the housekeeper. They were too preoccupied to wipe their feet. We’ll have to take off our shoes or we’ll track in some more.”

Tom peeked outside. “The path is all torn up and there’s an empty bottle smack in the middle of it. ”

Three steps led from the kitchen to the floor of the greenhouse. A modest difference in level in rollercoaster San Francisco. Tom was careful to avoid treading over the footprints. The soil was damp with the run-off from the beds. Vegetables, flowers, mixed up in abundance.

“You think Camacho paints still lifes?” Matt said. “Or is he one of these impressionist guys, green and fuzzy?”

“Maybe he just likes fresh salads.”

The greenhouse was packed with vegetation but wasn’t large. The greasy black thing among the pots was hard to miss. They both stepped into the beds to approach the scene. The body was a charred husk.

“He sure is fried,” Matt said.

It appeared to be a man, from the remains of sturdy, thick-soled boots. And the size of the corpse, even if it shrank in the blaze. A tool was next to the body, a tube with a cracked cylindric container attached to it, brass or copper, blackened with soot.

“My pop has one of these,” Tom said. “It’s an insect sprayer.” He pointed at the limp plants nearby. “For the tomatoes, I guess.”

“Accelerant?”

“Gasoline, possibly, various chemicals, all highly flammable. We should ask the housekeeper if Camacho was a smoker.”

“He sure liked his booze. Should check that empty bottle for prints,” Matt said.

Tom retraced his steps to the kitchen door, to the discarded bottle. He stared at the steps, at the grooves in the path. “Wanna hear what I think?” He badly wanted a cigarette but it was definitely not the place. “Here’s the theory. Camacho is stone drunk. He decides to take a stroll in his private paradise. He opens the kitchen door and tumbles down the greenhouse steps. See the nick on the edge here? He drops the bottle and lands hard on the path. You can see where his knees went, hands, feet. He scrambles to get up and makes a mess in the dirt.” The movie played in Tom’s head, frame by frame. “He lights a cigarette. Then, for some unfathomable reason, he decides to spray his tomatoes.”

“And goes whoof,” Matt said. “He’s a painter and his clothes have all that crud on them. Red-hot-whoof.” He smiled. “You’re good, you’re so goddam good.”

Noises were coming from the house. Voices raised. “Lots of assumptions in there,” Tom said. “Can the heat of a cigarette cause a fire so massive the guy has no time to run?”

“Ask all the idiots who manage to burn to death, in bed, with a smoldering cigarette falling on the mattress,” Matt said. “If he used a lighter, that’s an open flame. And if that insect sprayer leaked …”

Tom’s cogitations were interrupted by a bunch of cops jamming the kitchen door.

“What’s that, Keegan?” a beefy officer in uniform barked. “You tell one of my men I can’t come in? You’re shitting above your commode, boy. The Mission is my turf.”

“Wouldn’t dream of using your bathroom, sir.” Tom had seen that comedian before. In news photos, with microphones in front of his wobbly triple chin. He spotted the medical examiner standing behind the blowhard. “Securing the scene for you, doc.”

“Thank you, Detective,” the doc said. “I’ll take it from here. Come see me later. We’ll compare notes. I’d like a moment alone with the victim, now.”

Matt pushed through the kitchen door, parting the throng with forceful shoulders and sharp elbows. He crushed a few toes too, for good measure.

The housekeeper was still in the sitting room. Officer Brockwoods watched her cry.

“I tried to stop them,” he said.

“You did good.” Matt patted him on the shoulder.

Tom sat next to the housekeeper. “I’m so sorry you had to go through this. I have a few questions. Is it okay to talk now?”

She nodded, a hankie stuck to her face.

“Was Mr. Camacho a drinking man?”

She shook her head.

“We found an empty bottle in the greenhouse,” Tom said.

She looked up. “That’s because he finished the big painting.” She pointed at the hallway door. “It’s in the studio. It’s wonderful. I went to look at it this morning before I started working.” She buried her face in her hands.

Tom waited for the crisis to pass. “Mr. Camacho drinks when he completes a painting?”

“Each time. A celebration.” She wiped her eyes. “When he works, he only has water, maybe a glass of wine with dinner.”

“A disciplined man,” Tom said. “A smoker?”

“Cigarettes, like everybody.”

“Thank you. Officer Brockwoods will take your information. We’ll contact you if we need to talk to you.”

She sat there, eyes on the carpet, hands folded in her lap, holding the wet and bunched hankie.

“Find somebody to take her home, Brockwoods.” Tom motioned at Matt. “Let’s have a look at the studio before the hordes invade.”

The studio was a large room, with a wide floor-to-ceiling window. The painting the housekeeper mentioned was a symphony of emerald greens with slashing bursts of sun. The most beautiful thing Tom had ever seen.

Matt was not impressed. “I know where he got his inspiration. From the cabbages out there.” He used his handkerchief to pull two empty bottles of vodka from the dustbin. They were nestled in stained turpentine-reeking rags. “The man must have been so pickled he was swimming in it.”

Tom pulled out his crumpled pack of cigarettes. Two left. He popped one out, looked around for a lighter. “You think the place would go up in flames if I light up in here? See how fast that asshole in blue and his minions can move?”

Matt picked a box of matches from a shelf and tossed it to Tom. “I need some clean air. Paint fumes are getting to me.”

They walked back to the front door and out toward their car. The place was swarming with cops now, most of them with no good reason to be there. Neighbors were out on the sidewalk, in small groups, yakking.

“You write it up or I do?” Matt said. “Accidental incineration. Is that a category?”

“You do it, sport. One finger at a time tapping on that fucking keyboard. Call it accidental death. It’s easier to spell.” He stuck the cigarette in his mouth and slid the match box open. “I’ll be damned. Look at that.”

There were five burnt matches in the box, side by side with a bunch of live ones.

“I’ve heard of guys doing that,” Matt said. “That’s one bad habit that’ll burn a hole in your pocket.” He took a deep breath. “You think that did it?”

Tom struck a match, lit the cigarette, and blew out the flame. He let the burnt match drop to the pavement, and looked at it for a moment, pensive.

Then he crushed it under his heel.

My dad’s story was about an elderly artist who had the habit of sticking used matches back in the box … whoof. True? Yes, no? You decide. All I know is that there would be no Tom Keegan without it. And no Bop City Swing. Happy reading.

A Guest Post

I was invited on Donnell Ann Bell’s website for a post last week. It gives a bit of background on the text above. I talk about short story characters having what it take to drive a book. Here’s the link: When Short Story Characters Take a Leap.

I like these guys. Thanks for the tease, Martine. Off to Bop City.

Wonderful!